Unlike its predecessors, Konami’s Silent Hill 4: The Room coaxes the player away from the namesake town, changing the honored formula and permanently altering the series’ requirements. Besides distorting audience perception, the fourth game introduces a first-person viewpoint, interspersing the usual monstrosities with ghosts and establishing a limited inventory system, to name a few. Fans recognize the series’ essence within the theme of isolation; although gruesome horror and twisted psychology present less wondrously in The Room than prior titles, the game’s subtle achievements rival the likes of the celebrated Silent Hill 2: Restless Dreams. Unlike the latter, however, Silent Hill 4 does not concentrate its efforts on making the player feel wholly alone — quite the opposite, in fact.

As a series, Silent Hill’s energy traditionally draws from its backbone of psychological cunning and Japanese subtlety. The first game blames the town’s cult religion as the freakish activity’s root but wisely marks the occult phenomena as a mere precursor. The true power manifests from the depths of characters’ minds, laying the groundwork for series chills just as the surrounding fog emphasizes the blurred line between reality and dreams. But Silent Hill 4 departs from the usual darkness, removing many of its self-defined conventions such as the flashlight and sirens and clearing the veil shrouding the town’s mysteries. As gamers, we now stand on the edge, looking upon Silent Hill as an outsider; through that perspective we experience new psychological dangers perhaps more threatening than we initially realize.

The Room smothers us. No, I’m not talking about the awkward controls, the rushed déjà vu of the latter half, or even the horrendous decor of protagonist Henry Townshend’s apartment (well, maybe a little). Like Silent Hill 2, which drags us into hell with James Sunderland’s quiet madness and guilt, The Room continuously affirms our subordination to the merciless Walter Sullivan — an unpredictable serial killer determined to reunite with his "mother," whom he believes to embody room 302, Henry’s apartment. The more we learn about the 21 Sacraments ritual, and with each victim who dies, a number carved into his or her body, the more suffocated we feel. Quite brilliantly, The Room eliminates the only luxury made available in SH2: situational certainty. At least when James purged an area of monsters, we could then pause to wipe the sweat from our brows, even if Pyramid Head waited just around the next corner. We knew that with a little willpower and possibly some pants-wetting, we could survive or at least rest long enough to catch our breath. SH4 robs us of that comfort, alternatively instilling a hushed sense of urgency. Distancing us from the only characters with which we could possibly form a human connection, the game removes any potentially accessible control and reminds us that we’re under perpetual surveillance. The resulting effect achieves a paradox: We’re frightfully alone, but as vocalist Joe Romersa so brilliantly expresses in the game’s OST song, "Cradle of Forest": "It’s a great illusion / One never knows / When you think you’re really alone / Feel the eyes of someone looking in on you."

The characters of Silent Hill uphold a reputation for either being dreadfully forgettable or painfully memorable. The original lead, Harry Mason, was mundane and oblivious (perhaps allowing him a modicum of sanity) and SH2‘s James Sunderland proved inwardly troubled and vile. Almost anomalously, protagonist Henry Townshend defies either category. While not quite managing the dullness of Mason — Henry encounters a prostitute and meets a potential love interest — he lacks any tangible emotion or redemptive qualities. After five days, we discover him trapped in his room, the door chained from the inside and a confused Henry unable to establish successful contact with the world outside. Of course, a look inside the character’s life erases any semblance of surprise, for the life-altering change isn’t much of a change at all.

Most of the characters Henry meets in the various Otherworlds reside in his same apartment building, but they barely recognize him apart from being "that guy who lives in room 302." He lives next door to an attractive single woman, yet the two never exchanged more than a few words. Rather, the game offers and arguably encourages the player, as Henry, to spy on Eileen Galvin through the door’s peephole or a conveniently placed hole in the apartment’s wall. With an undeniable ability to make the paranormal and unnatural sound like ubiquitous affairs, Henry functions as a means to disinterest us simply because he reflects the theme of isolation, watchfulness, and often voyeurism — accurately represented by his photographic profession. Even after the locks break and the game concludes, only in one final scenario does Henry investigate a meaningful life endeavor. In most closing scenes, he rots in the same lousy apartment without ambition and, quite ironically, utterly alone. The destructive cycle that binds Henry originates before the chains even appear on his apartment door; the present situation orders Henry into a power struggle. Walter Sullivan’s ritualistic prophecy invites Henry into a sequence of Otherworlds, where he finally engages with his neighbors. As the protagonist learns about his purpose in the 21 Sacraments, he becomes emotionally close to Eileen Galvin; killing Sullivan embodies his efforts’ climax. Ironically, though, once the danger subsides Henry relinquishes that gained strength, and the invisible chains restricting him return.

The other characters also fail to impress us, instead seeming as former series composer Akira Yamaoka once stated, "a little weak." The sexually dominative Cynthia Velasquez hangs on Henry’s arm, flirting with him shamelessly as she cannot save herself. Jasper Gein stutters, suffering from mental instability; Andrew DeSalvo acts nervous and petulant; Richard Braintree demonstrates hostility and detests children. Eileen Galvin similarly tests our patience, for being required to protect her and maneuver despite her injuries quickly inspires gamer frustration. Each character shares a link with Walter Sullivan, who fluctuates between scheming composure and dangerous impulsivity.

Of course, the intensity of SH4 emerges from more than the characters’ natures — the unusual gameplay tactics and plot hold a considerable measure of terror, as well. The player must select each item wisely, decide whether to pin ghosts or rid Henry’s increasingly hellish apartment of hauntings, and connect with his room through an intimate first-person perspective. One can theoretically argue The Room as the most technically interactive of the Silent Hill titles, but the game lacks such interaction in a true sense. The player gradually turns aloof, and a feeling of doom replaces free will. Henry’s ritualistic role exponentially consumes his every move and waking moment, beginning with a hole that appears in his bathroom wall. Unable to abandon room 302, Henry must follow the widening hole where it leads, only leaving an Otherworld once the nightmare ejects him. Plus, the worth of independent travel through the Otherworlds erodes once the player realizes the act’s peril. Consecutive retreats to the apartment grant demonic spirits passage into Henry’s world, further opening the doors for Walter to penetrate reality. Soon the game’s only safe haven mutates into a playground for ghosts and strange phenomena; visiting your room later fails to restore Henry’s health, so in some cases the decision enacts more harm than good.

Nonetheless, every trip between dimensions unravels another layer of the 21 Sacraments and Walter’s ultimate plan. Bloody notes are slid under the door and scattered throughout the apartment, and the handwritten entries from room 302’s prior inhabitant suggest Henry’s inescapable fate, implying that he may be treading in someone else’s dead footsteps. The door, burdened with numerous locks, constantly reminds the player and Henry of the difficult tasks ahead; the windows are sealed, the phone dead, and Henry despairs as he futilely shouts to those beyond his walls. The story renders Henry as useless as the myriad ghosts, condemned to desperate and immortal existences only hindered by special implements found in Walter’s Otherworlds. The authority dwells with the enemy, and despite Henry’s endeavors he cannot save Walter’s many victims. Their ghostly presences irritate in terms of sound and visuals, simultaneously recalling Henry’s failure and possible future demise. Eileen offers Henry his ultimate chance to play savior, but obstructing her unwilling sacrifice amounts to Henry’s most challenging trial.

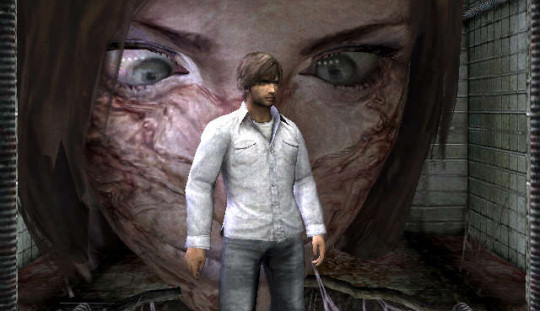

Both Henry and the player soon understand that, as Nietzsche once said, "He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you." One curious glance through the peephole reveals none other than Walter Sullivan eagerly reciprocating the gaze, a scene that unnerves because of the approaching destiny it entails. At one point, peering into Eileen’s room depicts Silent Hill’s amusement park mascot, Robbie the Rabbit, staring back. In the company of extreme haunting, players can look through the apartment’s window and spot a floating head quickly rise and disappear. Dozens of similar thematic incidents happen throughout the game: the water prison reeks of voyeurism in which Henry must participate. Indeed, he continuously delves into others’ private accounts and domains in order to stop Walter. However, the most shocking moment occurs in the hospital Otherworld. Henry enters a vacant room only to greet a disturbing version of Eileen’s head, eyes twitching and pursuing Henry’s every step. After delighting in numerous chances to watch Eileen, verging on sexual gratification, both Henry and the equally responsible player experience their own trespasses repaid. The game tempts the player with countless voyeuristic opportunities, without advertising them as necessities, and then exploits the indulgences as disgusting, sinful deeds. What prevents us, then, from expressing the same selfish, animalistic mannerisms of a serial killer? The game seems to distinguish Henry, a man of restricted initiative whom we know startlingly little about, from Walter on the basis of mere thought versus expressed action — a frightening suggestion.

Perhaps fulfilling Walter Sullivan’s delusion of room 302 as a mother figure, the game itself nurtures until physical and psychological suffocation, justifying the Silent Hill name. When maternal protection and safeguarding spirals into obsession and isolation ensues, the infliction becomes detrimental; likewise, room 302 threatens Henry’s survival, acting as a private retreat from the social world and oppositely representing the source of his suffering at Walter’s hands. The illusion of safety fades with the game’s progression, and the player’s attempts to reconstruct the shattered pieces are cheapened by the overwhelming reminder that every passing second connects to Walter’s ritual and the selected destinies erected because of it. Not even genuine emotion filters through the weak-willed protagonist Henry Townshend, whose unfulfilled life makes us wonder why he was chosen at all and whose every move is monitored by only sometimes unseen eyes.